I’ve only encountered the stifling smells and beige sights of NHS hospital food twice in my life. Once, as an eating disorder patient when – unlike other hospital admissions – ensuring a meal was at least edible was sort of the name of the game. The other time 15 years ago when, aged just 12 and a half, I saw my dad’s body ravaged by tumours until, eventually, he died a few days before my 13th birthday. It wasn’t all bad, though. My parents were too preoccupied to notice that their opportunist (brattish) children had forged their signatures in order for Eve to FINALLY get her ears pierced (I WAS 13 FFS), despite their strict instructions not to. Another flicker of light was the the mightily well-stocked hospice tuck shop. Like any other middle-class, north London child, my access to sweeties was cruelly limited. Apart from the birthday chocolate mum would buy as a I-don’t-know-what-else-to-buy-and-this-is-cheap present, most of my sugary treats were bought with my own hard-earned cash. Of which I had none. One of the few magical things that happens when one of your parents dies is that, for a good year, the rules to life no longer apply to you. In other words, I could raid that mother-fucking tuck shop whenever the hell I wanted. Well, when mum gave me a fiver and told me to ‘keep myself busy’. There is one particular haul I will never forget.

My dad always had a sensational appetite. When he went to Las Vegas with the lads lads lads he didn’t go to a single casino. Instead, he spent literally all his time in all-you-can-eat buffet restaurants. The only time I ever heard him shout was when he thought I’d stolen his extra large bar of fruit and nut, when in fact, mum had eaten it. Watching him unable to stomach even a teaspoon of his NHS finest puce-coloured mash or severely dehydrated chicken was heart-breaking. But it wasn’t the fault of the food – his mind wanted nothing more than that vomit-esque plate of rice pudding, but his body couldn’t. It could, however, enjoy Curly Wurlys, Jelly Tots and Fruit Pastilles. A week before he died I sat by his bedside as he helped me with my maths homework. Come 7pm, and having managed an eighth of his cottage pie (which was better than Wetherspoons’, to be fair), he handed me £3 and hurried me along to the tuck shop. I returned to his musky private room and we watched re-runs of A Place in The Sun whilst sharing miniature packets of Haribo Starmix, Jelly Tots and sugar-covered fruit gems. It was one of the last times I spent with dad, and undoubtedly the most precious.

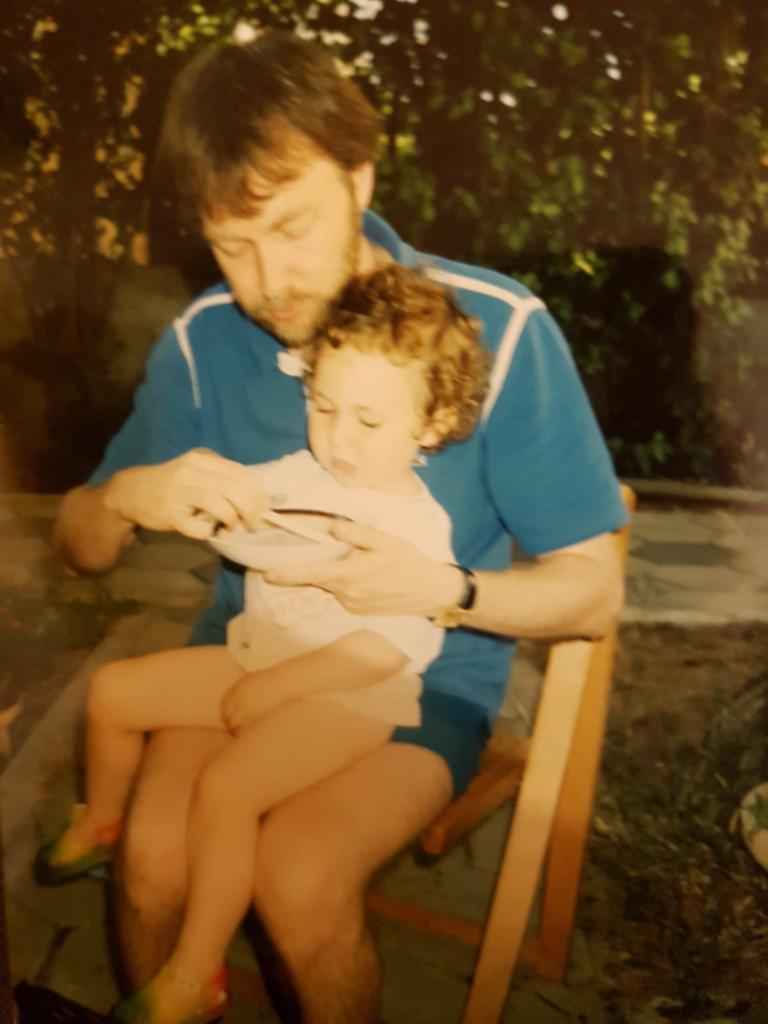

Dad, teaching me the art of eating chicken without spilling it between my cleavage. I’d say I’m 80% there.

Dad, teaching me the art of eating chicken without spilling it between my cleavage. I’d say I’m 80% there.

The point of my gushy preamble is not to make you feel sorry for the poor little middle-class girl who wasn’t allowed to eat sweets. Rather, it is to highlight the reality of eating during an NHS hospital or hospice admission, for many people. On hearing the latest revelations that three quarters of the food bought in UK hospitals is so-called ‘junk’, it seems natural to be outraged. The daily newspapers certainly are, along with ‘leading’ doctors who argue that hospitals should be ‘setting an example’ and that a blanket ban on sugary, fatty treats is a necessary intervention. Professor Dame Theresa Marteua, a health psychologist from the University of Cambridge said last month that the sale of high calorie snacks in hospital was: ‘hard to justify’ at a time when childhood obesity is rising and called for radical action. I have two problems with this line of incessant food shaming. Firstly, is there any evidence that so-called ‘junk’ food in hospital vending machines is making people fat? And secondly, given the NHS can’t even afford beds for sick people to sleep in, is this a legitimate priority?

Let’s address the facts. Firstly, the majority of British patients who spend time in hospital, overnight, do so for a very short space of time. According to the latest NHS Digital figures, the average length of stay in an NHS hospital is about four days. Thanks to surgical innovations over the past decade, roughly 35 per cent of all hospital admissions are day surgeries, meaning patients could return home that evening. So, would existing on chocolate bars and crisps for a few days, at perhaps one of the most terrifying times in your life, make much of a difference to your health?

‘It is important to distinguish between the diet someone has in hospital, and the diet they have at home, in day-to-day life,’ says Catherine Collins, Registered Dietitian who’s worked in various London hospitals. ‘The obesity problem we have is with people’s lifestyle and diet throughout their lives, not for the few days they might spend in hospital.’ What’s more, in nearly 60 per cent of hospital admissions, a procedure of some kind is involved. In roughly one in five of the 10 million operations performed in the UK every year, the digestive tract or respiratory tract are involved. Procedures which, according to Catherine Collins, who spent 20 years working in hospitals to feed post-op patients, make eating anything a near impossibility. Not to mention the appetite-suppressing general anaesthetic, which will likely be involved in at least 90 per cent of these admissions. ‘For most people in hospital, it is a challenge to get them to eat anything. Some people have a stoma bag following operations for bowel cancer or other digestive diseases which makes getting any food into them difficult,’ says Collins. The ‘healthiest’ choice for these patients? Crisps and full-sugar coke. ‘Stoma bags can make it difficult for the body to absorb water, leading to severe dehydration which can be very serious. The combination of sugar and salt helps the re-uptake of water, keeping the body hydrated. It’s also easy for patients to eat if they are lying sideways and struggling to sit up or even lie on their back,’ explains Collins.

‘Then there’s people with end stage renal disease, where kidneys are so damaged the person needs to have dialysis. These patients need a high calorie diet but too much protein makes urea build up in the bloodstream, leading to patient sickness. If potassium intake is too high – from vegetables, fruits and chocolate – could cause a heart attack if potassium because the kidney function isn’t there to remove it. Most people lose weight when they are in hospital. The task of most hospital dietitians is to get enough calories into people to build their strength up so they can go home. If patients can’t manage a full meal but can stomach a chocolate bar, it’s far better than nothing.’

Mediterranean hospital meals? A good idea, if they get eaten

The issue of hospital catering has long been debated, with various Governments attempting to reform the system over the years. If there’s anything to be said about hospital food it is this: generally speaking, it does not taste nice. But comprising new, Mediterranean diet-style menus is not as easy as it sounds. Firstly, it requires a significant chunk of the already squeezed NHS budget. Secondly, there is no substantial proof that patients will actually eat it. Collins says: ‘About 15 years ago, in St Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospital, they tried to change the catering to make it look more appetising, including a wide range of ingredients. But patients didn’t eat it. Hospital is overwhelming and scary for many people. They just want something they know is safe and familiar, like meat and two veg or cake and custard.’ Studies show that familiarity factor is a huge driver of nutrient intake in the hospital setting. Especially for older patients – the majority of the inpatient population. When a protein drink is mixed up within a bowl of vanilla ice cream, for instance, patients are much more likely to eat it.

View from yesterday morning then at tea time. Who says hospital food is bad 😁 pic.twitter.com/LzUEowPLNK

— Maureen Hall (@Maureen03526738) June 8, 2019

Even more concerning are the wealth of studies showing the soaring risk of malnutrition in older, hospitalised patients. One 2017 report published in the journal Nature estimated that around six of every 10 elderly people who go into hospital are at risk of malnutrition, with around 80,000 hospital meals left untouched every single day. Studies show that the reasons for this span far beyond the quality of the food. Specific dietary requirements, the time that a meal is served, lack of assistance from staff and even the background noise can all put patients off their (already unappetising) dinner. ‘By far the biggest risk in hospital is people not getting enough to eat which hinders their recovery,’ says Collins. The number of people dying in hospital as a direct result of malnutrition or dehydration is up a third since 2013. In 2017, almost 1000 British patients died as a direct result of problems consuming enough food and drink. As far as I am concerned, here lies the true scandal. And as someone who has been malnourished – and since fed back to health – I can confirm that supplying patients with their 10 a day will not solve this problem. Access to a familiar, comforting bar of Dairy Milk, containing plenty of all-important calories, will almost certainly help. After all, a Twix-a-day was pretty much my ticket out of hospital. As for visitors – friends, relatives, spouses – well, if there’s ever a time when we should let people take comfort in whichever way they please, it’s when their friend, relative or spouse is sick enough to require a hospital admission. It is only a few days. Plus, a few Curly Wurlys never killed anyone. Trust me.