Like most people who’ve endured the avalanche of crud brought about by a mental illness, I’ve often pondered the essential question: Why? Mum thinks it’s because my dad died, my therapist low-key blames my shitty school where the kids grew boobs 10 years before me, and I think…well, I’ve always just been a bit mental. This week I learned of another theory – suggested by one of the UK’s leading eating disorder psychiatrists. Three words: Ultra. Processed. Food (UPF).

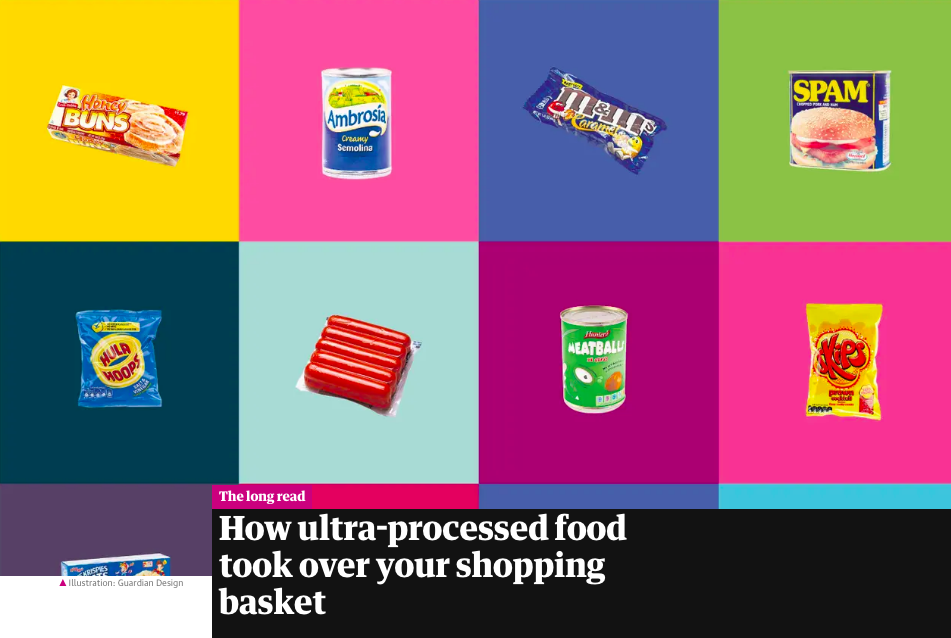

For those of you who are unfamiliar with this non-human garble, it means packaged, easy-to-cook food that poor people buy from Iceland. Oven chips was one example provided by said psychiatrist in one podcast on the subject. Apparently, the additives inside these devilish foods hijack the reward systems in our brains, resulting in an unhealthily dependent relationship. So, we either become emotionally attached to said foods – and therefore deny ourselves them when we hate ourselves – or eat so much we get fat, making us more likely to diet.

Dieting, as we all know, is one of the leading risk factors for the onset of eating disorders.

I’ll get into the ludicrousness of UPF shortly. But first: WTAF?! The last time I checked the three decades worth of research about the etiology of eating disorders, the general consensus was that this disease was, despite appearances, nothing to do with food at all. Yes, embarking on a diet can be a trigger. But what leads you to that diet in the first place – and what the outcome means to you – is caused by deep-rooted emotional havoc, which started sprouting somewhere along the way. Hence, the most effective treatments for long-term recovery involve strategies to manage emotional turmoil better – i.e a crap load of therapy.

Family therapy has proved to be particularly powerful, even for those who actually like their parents.

And, as anyone who has ever met anyone with an eating disorder will tell you, even the slightest inference that one food is better than another is like pouring cyanide on your coping strategies. Once we’ve learned the unhealthy connotations of any given ingredient, we cannot unlearn them. The voice in our heads whispering, ‘but what if’ every time we approach the supermarket shelf suddenly has permission to shout, drowning out our desires and, more importantly, our bodily cues. So you can imagine my horror when I heard this medical professional suggest that this theory could be helpful for treating people with eating disorders. Perhaps, she mused, we need to consider how each individual patient reacts to certain foods, and adjust their recovery plan accordingly.

I’m no medical professional. But I have met, at this point, somewhere in the region of 300 people who’ve had, or currently have, an eating disorder. And I cannot think of a single situation in which this wouldn’t be harmful. A host of studies show the first step to recovery is making peace with ALL food. Especially when it comes to anorexia – whereby restoring weight can be the difference between life and death.

Only when you can truly eat everything is it possible to know which foods you’d like to spend more time with, and those you’d rather not (Quavers).

More disturbing is that the commotion about the impact of ‘industrialised food’ (not my term) on the brain is all a bit fake-newsy. Firstly, most additives are derived from plants – citric acid, otherwise known as lemon juice, has it’s own E-number, for instance. Secondly, the evidence that such compounds can alter our sense of hunger and satiety is, at best, mixed. Most is done during animal experiments, and it’s almost impossible to ascertain if it’s the compound specifically that triggers reward signals, or just the presence of food itself. After all, humans are genetically attracted to all food.

But, they say, isn’t it a coincidence that chips, donuts and crisps – all produced in a…FACTORY (!) – are the most common binge foods? No. It’s true that no one binges on carrot sticks. But that’s not because carrot sticks are free from the toxic poison that lures us to consume our bodyweight in calories.

For one, sugary, fatty food is comforting. This is mostly due to associations made during childhood, when mum would give you a packet of your favourite biscuits to shut you up – and who can blame her? Also, most people with bulimia and binge eating disorder are not naïve as to the health risks of eating large quantities of high calorie food. For many, this is precisely the point – it is a desperate form of self-harm.

Whilst the incidence of bulimia and binge eating disorder may have risen in conjunction with the increased consumption of UPF, one does not necessarily cause the other. With the rise in chicken shops and greasy take away joints comes a drop in the number of residents who can afford to eat other, healthier (and pricier) food. Perhaps the surge in the popularity of ‘clean eating’ diets and the vilification of ‘treat’ foods might be a more sensible focus. Even I know that being told something is ‘bad’ just makes the lay person eat more of it – and I’ve only got one lowly psychology degree. And here’s another thought: instead of blaming foods for making people fat, how about we make being fat less of a stick to be beaten with? If inhabiting a bigger body wasn’t such a hate crime, dieting may become obsolete.

As for ‘ultra processed’, or ‘NOVA4’ food – as it’s been unhelpfully branded by our Government – well, it’s all a bit ridiculous, isn’t it? If you’re a single mum from Brixton with three fussy kids to feed and no time/energy to cook, a six-pack of burgers for £1.99 may well be your only viable option. If your priority is simply getting enough calories in your kids to last them through the following day, this may also be your healthiest option.

Similarly, if you haven’t eaten your recommended daily dose of bowel-boosting fibre – and the only carbs you have in the house is frozen chips – then a small portion is a healthy addition to the menu. Would vegan burgers – highly processed but full of bowel-friendly fibre and low-fat protein – be ‘bad’? What about baby food? Or cereal, fortified with essential vitamins and minerals and provider of the majority of British childrens’ key nutrients? Should we vilify fast-action yeast? Or baking powder? What about humous? Am I less likely to binge on a tray of chips if I’ve made them myself, using just three ingredients? Categorizing food in such a way is a blunt instrument when it comes to improving the variety of our diets.

It serves to make poorer people feel worse about themselves, and middle class shoppers smug that they’re made the ‘right’ choice. It misses the crux of the issue: Most people who eat lots of this food in fact do not have a choice. Viewing eating disorders via this lens is not just nuts – it’s risky. Too risky to justify further ‘experimental’ research on highly vulnerable people. The more we focus on the food, the further we are from understanding the truth about this devastating illness – which kills, by the way. Please give us credit – we are not empty vessels, too easily manipulated by cartoon characters on the back of cereal packets. We are human beings with feelings, thoughts, desires and needs which we struggle to accept. Any distraction is welcome – and food is as good as any.

If anyone has heard of this type of approach to ED treatment being trialed in patients, please get in touch at @notplantbased on instagram or notplantbased@gmail.com.